By Niki Irish

The very qualities that often define a successful lawyer — perfectionism, a relentless work ethic, and emotional armor — also pose grave risks to a lawyer’s mental well-being.

The statistics that speak to these risks are undeniable and alarming. Attorneys contemplate suicide at nearly twice the rate of the general population. While approximately 5 percent of U.S. adults report suicidal thoughts, studies indicate that 10 percent to 12 percent of lawyers have experienced them. A 2022 Law.com survey showed that nearly one in five legal professionals (19 percent) contemplated suicide during their careers.

The most striking finding from the 2023 report “Stressed, Lonely, and Overcommitted: Predictors of Lawyer Suicide Risk” underscores the deadly cost of the profession’s demands.1 Lawyers experiencing high stress are 22 times more likely to experience suicidal ideation than those with low stress, the report showed. Even intermediate stress increases the risk fivefold.

Unfortunately, these sobering statistics have not broken the culture of silence. Stigma and professional pressures still prevent lawyers from seeking help, as outward success often masks inner struggles. Mental health challenges are still too often viewed as liabilities rather than legitimate health conditions.

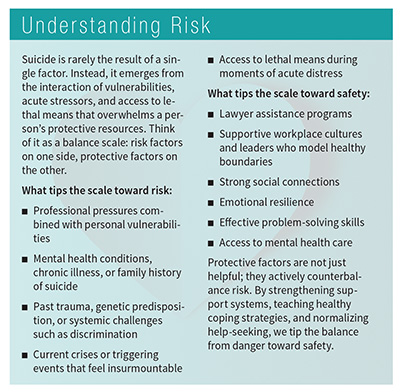

But the good news is that suicide is preventable, and the legal community has the power to save lives through awareness, intervention, and systemic change.

Why Legal Minds Are at Risk

The legal profession creates what mental health professionals often call a “perfect storm” of risk. Multiple factors converge to make attorneys uniquely vulnerable:

- Hypervigilance and pessimism. Legal training conditions lawyers to anticipate the worst, argue relentlessly, and never show weakness. This hypervigilance is psychologically exhausting when applied to every aspect of life, while the “never vulnerable” mindset actively prevents help-seeking.

- Perfectionism. The law is high stakes with demands for precision and flawless performance. The 2024 Lawyer Perfectionism & Well-Being Survey found that attorneys with high perfectionistic tendencies reported double the stress of their peers.2

- Overcommitment to work. Lawyers who struggle to disconnect from work are twice as likely to consider suicide, according to the 2023 report on lawyer stress. “Never enough” becomes the default mindset, leaving little room for rest or balance.

- Isolation. Despite working alongside colleagues, attorneys often feel profoundly alone. Client confidentiality, competitive cultures, and adversarial work create emotional barriers. The same 2023 study showed that lonely lawyers are almost three times more likely to experience suicidal thoughts.

- Substance use. A 2016 study, “The Prevalence of Substance Use and Other Mental Health Concerns Among American Attorneys,” reported that lawyers are nearly twice as likely as other Americans to struggle with alcohol or substance abuse.3 What often begins as stress management can become a dangerous coping mechanism that compounds suicide risk.

- Amplified stressors. Post-pandemic disconnection, student loan burdens, economic and political uncertainty, and rapid technological change add to an already heavy load.

Recognizing Warning Signs

Recognizing Warning Signs

Suicide rarely occurs without warning, though it can feel sudden to those left behind. Most individuals who die by suicide exhibit signs beforehand. Lawyers, trained to project competence, may mask their struggles in professional settings while revealing subtle changes to those closest to them.

Spouses, friends, and trusted colleagues are often the first to notice. If you are worried, talk with others who know the person; multiple perspectives can reveal patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Although there is no formula, certain behavioral, mood, and verbal cues rightly raise concern, especially when they represent a change from someone’s usual baseline. Behavioral red flags include missed deadlines or appointments, social withdrawal, reckless behavior, increased alcohol or drug use, changes in appearance, giving away possessions, or making unusual financial arrangements. Mood indicators are irritability, depression, rage, apathy, anxiety, humiliation, or sudden unexplained happiness after depression. Examples of language clues include expressions of hopelessness (“What’s the point?”), being a burden (“Everyone would be better off without me”), or being trapped (“I can’t do this anymore” or “I want the pain to stop”).

Trust your instincts. When you sense something’s wrong, it probably is. It is better to risk an awkward conversation than live with regret. Don’t wait for someone else to step in; you may be the only one who will.

Having the Lifesaving Conversation

Approaching a colleague in distress can feel intimidating, but silence is far more dangerous than discomfort. Remember: You are not their therapist. Your role is to show genuine care and connect them to help.

Preparation can make a critical difference. Familiarize yourself with available resources, such as your state’s lawyer assistance program, the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, or local mental health services. Choose a private, uninterrupted setting for the conversation. Ground yourself beforehand and stay centered throughout; take deep breaths, steady your body, and remind yourself that you can influence their decision, but you cannot control it. Keep these guiding principles in mind when speaking with a colleague in distress:

- Validate their experience. Their pain is real, even if you don’t fully understand it.

- Listen, don’t fix. Your role is to hear them and connect them to resources, not solve the problem.

- Remain nonjudgmental. Avoid debating whether life is worth living or minimizing their experience.

- Practice empathy. Use both words and body language to show support and concern. Your presence matters much more than perfect responses.

The hardest part is often starting the conversation. Genuine observation and concern work well, such as “I care about you, and I’ve noticed you’re working even later than usual and seem more on edge during meetings. How are you doing?” or “You mentioned feeling trapped the other day, and that really concerned me.” Or, “I’ve had times when I struggled, and talking to someone helped. You don’t have to face this alone.”

As they respond, listen actively. Ask open-ended questions and reflect back what you hear. Validate their pain with statements like “This sounds incredibly difficult” or “Thank you for trusting me with this.” Avoid minimizing phrases such as “Everyone has tough times” or “This too shall pass,” which can heighten feelings of isolation and shut down the conversation.

It is also important to ask about suicidal thoughts. Research confirms that asking directly does not increase the risk of suicide.4 It shows care and can bring relief. Prepare questions in advance and get comfortable with phrasing until it becomes less awkward. Examples include: “How long have you been feeling this way?” and “Sometimes when people feel like this, they think about ending their life. Are you having those thoughts?” If you can be more direct, ask “Are you thinking about killing yourself?”

If the conversation feels beyond your comfort level, you can still help. Try saying, “I may not have the right words, but I want to connect you to someone who can help.” Then share resources or offer to accompany them to a professional.

When to Take Emergency Action

Knowing when to move from support to immediate intervention is critical. Begin by assessing risk: Does the person have a plan, access to means, or a clear timeline for acting on suicidal thoughts? If the answer is yes, treat the situation as an emergency. Stay with the person and call 988 together. If you believe there is imminent danger, call 911 or the local mobile crisis line. When making that decision, remember that individuals from marginalized communities may feel more at risk with police intervention. Whenever possible, take steps to restrict access to lethal means.

If danger is not imminent, provide resources and encourage professional help. Offer to walk with the individual throughout the process, literally or figuratively.

The most powerful tool you have is time. Creating space between the moment of crisis and potential action allows overwhelming feelings to subside and opens the door for help. Your caring presence during this critical window can make all the difference.

Caring for Yourself and Those in Need

Conversations about suicide can be heavy. Debrief with a trusted colleague or friend and allow yourself time to rest and recover. Grounding techniques such as deep breathing, mindfulness, or gentle physical activity can help calm your body’s fight-or-flight response.

Remember that you can influence someone’s decision to seek help, but you cannot control their ultimate choices. That responsibility is theirs, not yours. Giving yourself permission to step back and care for yourself is essential for your own mental health and for continuing to support others effectively.

Supporting someone who has survived a suicide attempt or who is actively struggling requires ongoing compassion, patience, and understanding. Follow their lead: Some individuals find it helpful to talk about their experiences, while others may need space. Maintain regular, low-pressure contact through simple gestures such as a brief “thinking of you” message, without imposing expectations.

Avoid treating them differently; many survivors fear being defined by their crisis. Respect their recovery timeline. Healing is not linear, and setbacks do not mean failure. Encourage professional support but remain patient if they are not ready to seek help. Attend to your own needs by drawing on your support systems.

Most importantly, continue to be present without trying to “fix” them. Your consistent, nonjudgmental presence communicates that their life has value, even when they may struggle to see it themselves.

Postvention: After a Suicide Loss

If the unthinkable occurs, the loss brings a unique and often complicated form of grief. For colleagues, friends, and family, the experience can feel isolating, and stigma may intensify the pain. Every person’s grief journey is different, and there is no single “correct” way to respond; what matters most is respecting the individual’s personal experience.

Organizations play a critical role through structured, compassionate support after a suicide, known as postvention. Done well, postvention supports those directly impacted, reduces the risk of contagion, and fosters a healthier environment for survivors. Resources such as the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention’s Postvention Toolkit for Workplaces can guide legal organizations in developing thoughtful protocols that acknowledge grief, reduce stigma, and offer tangible support to affected colleagues.

By prioritizing postvention, the legal profession can help survivors navigate grief safely while building a culture that takes mental health seriously and values the well-being of every member.

Building a Safer Profession

To truly protect professionals, legal institutions can embed protective factors into their culture. This includes fostering authentic connections, prioritizing balanced workloads, reducing alcohol-centered socializing, investing in comprehensive mental health training and resources, and normalizing help-seeking behaviors. Leadership can model healthy boundaries, showing that caring for mental health is not a weakness but a professional responsibility.

Individual lawyers can play their part by giving themselves permission to set boundaries, seeking help when struggling, and genuinely caring for colleagues as human beings, not just professional contacts. Check in on one another, model healthy behaviors, and speak openly about mental health.

Suicide prevention is not about having all the answers. It is about courage, compassion, and connection. It is listening without judgment, offering support, and connecting people to help and resources. In a profession devoted to defending others, the most urgent fight may be the one to save a colleague’s life.

If you or someone you know is struggling with thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 to connect with the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. Confidential help is available 24/7.

Niki Irish, outreach and education coordinator for the D.C. Bar Lawyer Assistance Program, has 20 years of experience in mental health and addiction and is a licensed clinical social worker in the District of Columbia. Email [email protected] if you need free, confidential mental health support.

Notes

1. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9956925.

2. https://nalp.org/uploads/2025JuneBulletinPerilsofPerfectionism.pdf.

3. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4736291.

4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24998511.