Ask an Expert

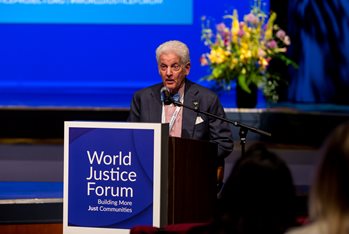

Defining & Quantifying Rule of Law: World Justice Project CEO Bill Neukom on Why It Matters

October 28, 2022

In a livestream event held on October 26, World Justice Project issued its annual Rule of Law Index showing global declines in rule of law for the fifth consecutive year. The United States saw some improvement in this year’s index, a partial recovery from a recent slump in numbers, though the country’s score remains below 2020 levels.

The index gathers survey data from 140 countries and jurisdictions globally to assess their adherence to rule of law principles. This year’s report comes from surveys of more than 150,000 households and 3,600 legal practitioners and experts around the world.

World Justice Project was cofounded by William H. Neukom in 2006 as a presidential initiative launched during his term as president of the American Bar Association (ABA). Neukom continues to lead the organization’s efforts in his role as CEO, working to draw attention to rule of law issues both domestically and abroad.

The D.C. Bar spoke with Neukom about what rule of law means, how it is measured, and why World Justice Project’s efforts matter.

How did you come to be interested in rule of law issues?

It starts with my practice here in Seattle. Although I concluded my active practice as the lead lawyer for Microsoft for almost 25 years, prior to that I had a very diverse practice. My practice began with a firm that was an advocate for the underdogs. It was an unusual opportunity, maybe only possible back in the ’70s, to represent a wide range of clients and a wide range of community organizations and initiatives in Washington state.

In the course of that, I represented criminal defendants, the best that I could, both in state and federal court. I did some family law with all of its agony, with custody and the like. I did a fair amount of civil rights work. The Seattle Seven defense team was in our office, for example. It was a really distinctive practice. It gave me a sense of the wide range of imperfections in what I call the legal process, even in the get-along, go-along community of the Seattle ’70s.

During my 25 wonderful years with Microsoft, there was a good deal of travel, as you might imagine. The offshore markets were the ones where one could earn market share and earn revenues, so I visited a lot of countries, including, during the end of my practice, developing countries, because that’s where the opportunities led for a software company.

When I left Microsoft in late 2002 and came back to the firm, I had a chance to reflect a bit and I made the mistake of considering running for president-elect of the ABA. I knew that every ABA president has a chance to pick a theme or a topic for a presidential project, and I’ve seen better lawyers than I pick a project that never survived beyond their year as immediate past president. I wanted to initiate something that had staying power.

Happily, I was unopposed, the only chance I would have had to win, so I had a chance to reflect. Considering what I had seen around the world, in Seattle, and around the U.S., I kept coming back to the question of why some communities seemed to be more functional and more viable than other communities. What is the key element? In the course of ruminating about that and discussing the topic with other lawyers and scholars, I came around to the notion of rule of law, as we define it, as the fundamental element of a functioning society.

How do you define rule of law?

Our definition, which we created in consultation with hundreds of experts around the world, is that rule of law is a system made up of laws, institutions, norms, and community commitment. The definition of rule of law accommodates different forms of government. Rule of law can exist under a benign dictatorship, a parliamentary monarchy, or a western liberal democracy.

A rule of law system has to deliver four things to the members of the community. First, it has to deliver accountability. This is accountability of both private and public actors. Second, the system must have just laws that include protections for human rights, due process, property rights, and contract rights. Third, the system has to be one of open government, where we, the governed, get to watch law created, administered, and enforced. A final universal rule of law principle is accessible justice. By this we mean accessible, impartial dispute resolutions, conducted either formally or informally, in both civil and criminal matters.

Our definition of the term is, by far, the one most often cited on the web, and I don’t think any other definition better captures what Tom Carothers calls “this capacious concept of the rule of law.” We’ve invested a lot of effort into developing the definition. If I had one wish it would be that any time someone uses the term “rule of law,” which has become cliché in political and government discourse these days, it would be followed with “by that I mean….” Some definitions fail to capture the full landscape, while others leave out accountability, for example, which is a huge mistake, it seems to us.

Why does World Justice Project produce the index?

One of the very first things we did at World Justice Project was ask ourselves what we were looking to accomplish. We came up with the notion of three pillars: academic activity, data gathering and analysis, and engaging with local rule of law actors.

For the first pillar, we knew that to be taken seriously in conversations about rule of law, we needed some cornerstone of intellectual merit. We recruited a roster of world-class scholars who had devoted some of their time and energy to the study of the rule of law. And we have developed strategic relationships with a number of academic institutions, including Stanford Law School and Dartmouth College, among others. As for the third pillar, we have developed and supported a network of hundreds of local organizations around the world working to advance the rule of law in their communities.

So that leaves the second pillar: rule of law data. As we were starting, we thought, as a lot of wise people say, if you can’t define it, you can’t measure it, and if you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it. We often consider things in terms of meaning, measuring, and mattering. In terms of measuring, we asked whether there was a viable source of data available that could talk about the real-world role of the rule of law and the consequences of a lack of rule of law.

There was not. So, we recruited Juan Botero and Alejandro Ponce from the World Bank who, along with [World Justice Project Vice President] Mark Agrast, designed the index and its methodology, which has since been tested all around the world. We conduct household interviews of a thousand randomly selected people in a given country. We even interview them in dialect; it’s easily the most expensive part of our work. We ask interviewees about very real-world quotidian experiences relating to rule of law, gather the data, and then triangulate this with responses from qualified experts in that country, mostly lawyers, who contribute their observations about the legal system and processes.

Finally, we pause and use our peripheral vision to take a look at other databases that include rule of law data to ensure that we aren’t wildly off from what they claim they have gathered, as a checkpoint on our own data. We pull all of that together, and that’s what gives us the opportunity to present the results in the index.

We are very intentional about how we use the data. We’re not scolding or passing judgment. We simply provide the data. As we’ve matured, we’ve gotten to the point where, if we’re careful, and don’t in any way compromise the accuracy and the objectivity of our data, we can analyze that data and come away with conclusions and themes from the data. Then that becomes even more valuable to the governments we study, the press, businesses, civil society organizations, the academy, and the others that have a role in advancing the rule of law for the well-being of folks in the community.

How can organizations and individuals support rule of law domestically and abroad?

The amazing D.C. Bar, and other bar associations, might decide that Law Day, May 1, could be celebrated as “Rule of Law Day” and hold an event or series of events inviting practitioners, their clients, and the community to consider how rule of law, as we define it, is not just fundamentally important, it is foundationally important. It is the underpinning of communities of opportunity.

It’s important to be clear that this is not the rule of lawyers and judges. Yes, we have an insight into the systems, and we are practitioners, but rule of law is just as important to faith leaders, teachers, artists, and businesspeople as it is for lawyers and judges because it is the foundation of their livelihood and their well-being.

Rule of law is why you can feel safe in your home. It’s why you can earn a living and, perhaps, create enough wherewithal to send your daughter to college. What does all that rely on? If you strip out rule of law, what you are left with is a flimsy foundation on which to build a life.

How do you see World Justice Project’s work continuing to develop?

We are now perfecting our ability to do an index at a subnational level. We got some [Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs] funding to conduct a subnational survey in Mexico, where we have already produced a national survey a couple of times. We learned three things.

First, the closer the data is to the people affected, the more they care and seek reform. A report about corruption on the national level might cause dismay, but a report about local corruption really gets people’s attention and motivates them to make change. Next, local data also gets the attention of local officials. Governors are as competitive as anyone else, and they will want to compare favorably to their peers. Finally, the national government, looking at the crazy quilt of data we have provided them, can ask themselves where they might intervene in a constructive fashion.

We’ve taken that learning to the EU, where we’ve just embarked on doing a subnational index for the EU countries. We’ll be looking at the rule of law in the subnational regions that the EU uses to analyze and address regional differences across the Union. We are in the process of doing that study right now.

If I could wave my magic wand, I would have the Department of Justice fund us tomorrow to start a state-by-state index because the way that prisons work in Mississippi may be different from the way they work in Washington state, and the discrimination within the civil system may be different in Alabama than it is in California, for example. The differences in rule of law between states would come to the surface, I think, with a subnational index of the United States, during a time in which we surely need it.